The choice between a monolithic and a microservices architecture is one of the most critical decisions a software engineering team faces. It impacts everything from development velocity and team structure to operational complexity and scalability. For Site Reliability Engineers, Software Engineers, and Software Architects, understanding the nuances of these paradigms is paramount to designing resilient, performant, and maintainable systems. This article delves deep into the architectural trade-offs, providing practical guidance, exploring anti-patterns like the distributed monolith, and outlining effective migration strategies to help you make the right choice for your organization.

The Monolithic Architecture: Simplicity and Its Constraints

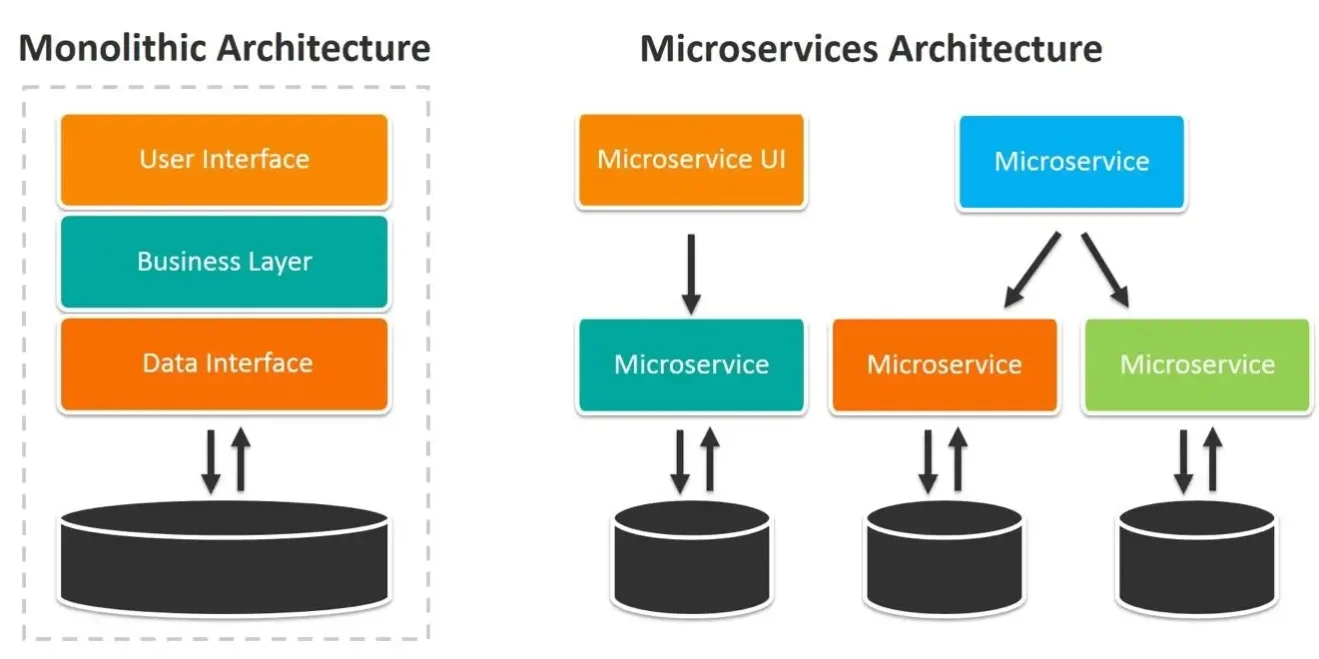

At its core, a monolithic architecture refers to a single, indivisible unit of software. All components—the UI, business logic, and data access layer—are bundled into a single application and deployed as a single process. This traditional approach has been the bedrock of software development for decades.

Defining the Monolith

Imagine a typical e-commerce application built with Ruby on Rails or Spring Boot. All features, from user authentication and product catalog management to order processing and payment gateways, reside within a single codebase. This application is compiled into a single executable or archive (e.g., a JAR or WAR file) and deployed to a single server or cluster of servers running the same application instance.

Advantages of Monoliths

- Simpler Development (Initially): For small teams and applications, the monolithic approach is straightforward. All code is in one place, making it easier to manage dependencies, refactor, and understand the entire system’s flow.

- Easier to Deploy: There’s only one application to deploy, simplifying the CI/CD pipeline and reducing operational overhead.

- Simplified Testing: End-to-end testing is often easier to set up as all components are part of a single process.

- Unified Observability: Centralized logging, monitoring, and debugging are often simpler since all actions occur within a single application context.

- Atomic Transactions: Database transactions spanning multiple operations are inherently easier to manage, ensuring strong consistency without distributed transaction complexities.

Disadvantages of Monoliths

- Scalability Limitations: The entire application must be scaled together, even if only a small part experiences high load. This can be inefficient and costly.

- Technology Lock-in: Once a technology stack is chosen, it’s difficult to introduce new languages or frameworks for specific features without rewriting large portions of the application.

- Slower Development Cycles: As the codebase grows, compilation, testing, and deployment times increase. Developer onboarding can become challenging due to the sheer size and complexity of the codebase.

- Increased Risk for Deployments: A small bug in one module can potentially bring down the entire application. Rollbacks can also be complex.

- Difficulty with Refactoring: Due to tight coupling between modules, making significant changes or refactoring can introduce unexpected side effects across the system.

Note: While monoliths are often associated with legacy systems, a well-architected modular monolith with clear internal boundaries and interfaces can still be a highly effective solution for many modern applications, especially in their early stages.

The Microservices Architecture: Distributed Power and Its Pits

The microservices architectural style structures an application as a collection of loosely coupled, independently deployable services, organized around business capabilities. Each service owns its data and communicates with others via well-defined APIs.

Defining Microservices

Continuing the e-commerce example, in a microservices setup, you would have separate services for `User Management`, `Product Catalog`, `Order Processing`, `Payment Gateway`, and `Inventory`. Each service would be developed, deployed, and scaled independently, potentially using different technologies. For instance, the `Product Catalog` might use a NoSQL database for flexible data schemas, while `Order Processing` might use a relational database for transactional integrity.

Key characteristics of microservices include:

- Single Responsibility Principle: Each service focuses on a single business capability.

- Loose Coupling: Services interact through well-defined APIs (REST, gRPC, message queues) and are not aware of each other’s internal implementation details.

- Independent Deployability: Each service can be deployed, updated, and scaled without affecting other services.

- Data Ownership: Each service typically owns its data store, avoiding shared databases that can become bottlenecks and introduce tight coupling.

- Decentralized Governance: Teams have autonomy over their services’ technology stack and development processes.

Advantages of Microservices

- Independent Scalability: Individual services can be scaled up or down based on demand, optimizing resource utilization.

- Technology Diversity (Polyglot Persistence/Programming): Teams can choose the best language, framework, and database for each service’s specific requirements.

- Faster Development Cycles: Smaller codebases are easier for teams to understand and develop, leading to quicker iterations and deployments.

- Improved Fault Isolation: A failure in one service is less likely to bring down the entire application, enhancing overall system resilience.

- Easier to Refactor and Upgrade: Small services are easier to refactor, upgrade, or even rewrite entirely without impacting the rest of the system.

- Team Autonomy: Aligns well with small, cross-functional teams, allowing them to work independently and own their services end-to-end.

Disadvantages of Microservices

- Increased Operational Complexity: Managing a distributed system with many services introduces challenges in deployment, monitoring, logging, service discovery, configuration, and networking.

- Distributed Data Management: Achieving transactional consistency across multiple services is complex, often requiring eventual consistency patterns (e.g., Saga pattern) which introduce new design considerations.

- Inter-service Communication Overhead: Network latency, serialization/deserialization, and potential communication failures must be handled.

- Debugging Challenges: Tracing requests across multiple services can be difficult without robust distributed tracing tools.

- Higher Initial Infrastructure Investment: Requires sophisticated CI/CD pipelines, container orchestration (Kubernetes), API gateways, service meshes, and robust observability tools.

- Security Concerns: More network endpoints introduce a larger attack surface, requiring robust authentication and authorization mechanisms across services.

When Microservices Make Sense (and When They Don’t)

The decision isn’t about which architecture is inherently “better,” but which is more appropriate for your specific context.

When to Lean Towards Microservices

- Large, Complex Applications: For systems with extensive and diverse business domains that can be logically broken down into independent services. Examples: Netflix, Amazon, Spotify manage hundreds or thousands of microservices.

- High Growth and Traffic Projections: If your application needs fine-grained scalability to handle unpredictable or rapidly increasing loads on specific parts of the system.

- Independent Team Autonomy and Parallel Development: When you have multiple, autonomous teams working on different features simultaneously, without stepping on each other’s toes. This aligns with Amazon’s “two-pizza team” philosophy.

- Mature DevOps Culture and Distributed Systems Expertise: Your organization must have the operational maturity, tooling, and skilled personnel to manage the inherent complexity of distributed systems.

- Requirement for Technology Diversity: If different business domains truly benefit from different programming languages, frameworks, or data stores.

- High Fault Tolerance Requirements: When the application needs to remain partially functional even if some components fail.

When to Stick with Monoliths (or Start with Them)

- Small to Medium-Sized Applications: For applications with a limited scope, a monolith is often simpler, faster, and cheaper to build and maintain.

- Startups or Small Teams: When resources (time, money, personnel) are limited, a monolith provides quicker time-to-market and lower initial operational overhead. Focus on proving the business model first.

- Proof-of-Concept or MVP Development: For initial prototypes or minimum viable products, the priority is often rapid iteration and deployment, which monoliths facilitate.

- Tightly Coupled Business Logic: If your application’s business logic is inherently intertwined and difficult to decompose without creating a “distributed monolith” (more on this below).

- Lack of DevOps Maturity or Distributed Systems Experience: Trying to adopt microservices without the necessary cultural and technical readiness can lead to significant pain and failure.

- Compliance/Regulatory Constraints: In some highly regulated environments, a single codebase can simplify audits and compliance procedures.

Recommendation: Many successful companies advocate starting with a “Monolith First” approach. Build a modular monolith, and only break it down into microservices when the pain points (e.g., scaling bottlenecks, deployment contention, team velocity degradation) become significant enough to justify the increased complexity.

The Distributed Monolith Anti-Pattern: A Worst-of-Both-Worlds Scenario

The allure of microservices can sometimes lead teams down a perilous path: building a distributed monolith. This anti-pattern reaps the disadvantages of both architectures without enjoying the benefits of either.

What is a Distributed Monolith?

A distributed monolith refers to a system composed of multiple services that appear to be microservices but are fundamentally coupled, lacking true independence. They are distributed in deployment but monolithic in their design and behavior. Characteristics include:

- Shared Database Across “Services”: Multiple services directly access and modify the same database, leading to tight coupling at the data layer.

- Synchronous, Chatty Inter-Service Communication: Services make frequent, synchronous calls to each other, creating long request chains and making individual services unable to function without their dependencies.

- Coordinated Deployments: Changes in one service often necessitate changes and simultaneous deployments in several others, negating the independent deployability benefit.

- Lack of Clear Bounded Contexts: Services are not truly encapsulated around business capabilities; instead, they might represent technical layers (e.g., `UserService`, `ProductService`, `OrderService` all manipulating a common `Customer` table).

- Single Point of Failure/Bottleneck Hidden in Distributed Complexity: While services are separate, a bottleneck in one (often the shared database) can bring down the entire “distributed” system.

Why it Happens

The distributed monolith typically arises from:

- Naïve Migration: Attempting to break down a monolith by simply splitting it into multiple services without understanding domain-driven design principles or the implications of data ownership.

- Applying Monolithic Thinking: Developers accustomed to a monolithic environment carry over practices like shared data models or tight synchronous coupling to a distributed context.

- Fear of Data Duplication: An aversion to duplicating data (which is often necessary for data autonomy in microservices) leads to services sharing a single database.

- Lack of Domain-Driven Design (DDD) Expertise: Without clear bounded contexts and ubiquitous language, it’s hard to define truly independent service boundaries.

Consequences

The distributed monolith is a worst-of-both-worlds scenario:

- Increased Operational Complexity Without Benefits: You get the headaches of distributed systems (networking, latency, debugging) but none of the advantages (independent scaling, fault isolation, team autonomy).

- Debugging Nightmares: Tracing issues across tightly coupled, synchronously communicating services is incredibly difficult.

- Development Slowdowns: Despite having “microservices,” teams are constantly blocked by dependencies on other teams for shared data structures or coordinated deployments.

- Performance Bottlenecks: Shared databases become choke points, and synchronous communication chains introduce significant latency.

- Leads to Disillusionment: Teams blame microservices for problems actually caused by poor design, leading to a negative perception of the architectural style.

Consider this simplified example of a distributed monolith:

# service_a.py (e.g., User Service)

from shared_db import get_db_connection

def create_user_and_order(user_data, order_data):

db = get_db_connection()

cursor = db.cursor()

# Insert into users table

cursor.execute("INSERT INTO users (name, email) VALUES (?, ?)", (user_data['name'], user_data['email']))

user_id = cursor.lastrowid

# Directly insert into orders table, owned by 'Order Service'

cursor.execute("INSERT INTO orders (user_id, item, quantity) VALUES (?, ?, ?)",

(user_id, order_data['item'], order_data['quantity']))

db.commit()

db.close()

return {"user_id": user_id, "order_status": "created"}

# service_b.py (e.g., Order Service)

from shared_db import get_db_connection

def get_order_details(order_id):

db = get_db_connection()

cursor = db.cursor()

# Joins across tables owned by 'User Service' and 'Order Service'

cursor.execute("SELECT o.id, u.name as user_name, o.item FROM orders o JOIN users u ON o.user_id = u.id WHERE o.id = ?", (order_id,))

order_details = cursor.fetchone()

db.close()

return order_details

# Both services depend on 'shared_db.py' and have direct knowledge of each other's data schema.

# Any schema change in 'users' or 'orders' tables requires coordinated changes and deployments in both services.

In a true microservices setup, `UserService` would own the `users` table, and `OrderService` would own the `orders` table. `UserService` might emit an event (`UserCreatedEvent`), which `OrderService` would consume to create an order, or `OrderService` would call an API on `UserService` to get user details, never directly touching the `users` table.

Migration Strategies and Organizational Readiness

Migrating from a monolith to microservices is not merely a technical undertaking; it’s an organizational transformation. It requires careful planning, iterative execution, and significant changes in team structure and operational practices.

Monolith to Microservices Migration Strategies

A “big bang” rewrite is almost always a bad idea for existing, complex monoliths. Instead, incremental approaches are preferred:

-

The Strangler Fig Pattern:

- Concept: Inspired by the strangler fig vine, which grows around a host tree, this pattern involves gradually replacing parts of the monolith with new microservices. A façade (often an API Gateway or a reverse proxy) redirects traffic from the monolith to the new services as they come online.

- Benefits: Incremental, reduces risk, allows existing functionality to remain operational, and provides continuous value delivery during migration.

- Example: Start by extracting a stable, well-defined module like user authentication or payment processing into a new microservice.

# Nginx as a reverse proxy server { listen 80; server_name myapp.com; # Route /auth requests to the new Authentication Microservice location /auth { proxy_pass http://authentication-service; proxy_set_header Host $host; proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr; } # All other requests still go to the Monolith location / { proxy_pass http://monolith-service; proxy_set_header Host $host; proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr; } }

-

Branch by Abstraction:

- Concept: This pattern is often used internally within the codebase. You create an abstraction layer over a module you intend to extract. New functionality is then implemented in the microservice, and the monolith calls this new microservice through the abstraction. Once completely replaced, the old monolithic code path is removed.

- Benefits: Allows for safe, gradual migration of specific functionalities.

- Example: Abstracting a payment processing module. The monolith’s `PaymentGateway` interface is implemented by `OldMonolithicPaymentService` and `NewMicroservicePaymentProxy`. A feature flag or configuration determines which implementation is used.

-

Decomposition by Business Capability:

- Concept: Identify clear business domains (bounded contexts) within the monolith and extract them as independent services. This often requires significant refactoring to untangle dependencies.

- Benefits: Leads to truly independent services aligned with business value.

- Challenge: Requires strong domain-driven design expertise and courage to refactor.

Organizational Readiness: Beyond the Code

Successful microservices adoption hinges on organizational alignment and capability more than just technical prowess.

-

DevOps Culture and Automation:

- Requirement: A mature DevOps culture is non-negotiable. Microservices demand robust CI/CD pipelines, automated testing, infrastructure as code (IaC), and automated deployments for each service.

- Why: Manual processes will quickly become a bottleneck and source of errors when dealing with dozens or hundreds of services.

-

Team Structure (Conway’s Law):

- Requirement: Your organizational structure should mirror your desired architecture. Small, autonomous, cross-functional teams (e.g., “you build it, you run it”) that own a set of services end-to-end.

- Why: Breaking down monoliths without breaking down monolithic teams leads to a distributed monolith.

-

Monitoring and Observability:

- Requirement: Comprehensive tools for centralized logging (ELK stack, Splunk, Loki), metrics collection (Prometheus, Grafana), and distributed tracing (Jaeger, Zipkin, OpenTelemetry).

- Why: Debugging issues across multiple services without full visibility is a nightmare. SREs need rich data to understand system health and troubleshoot.

-

Communication Patterns:

- Requirement: A strategy for inter-service communication. This often involves synchronous APIs (REST, gRPC) for requests, and asynchronous messaging (Kafka, RabbitMQ, SQS) for event-driven architectures. API Gateways centralize routing, authentication, and rate limiting. Service meshes (Istio, Linkerd) manage inter-service communication, traffic management, and security.

- Why: Well-defined communication contracts and robust messaging infrastructure are vital for loose coupling and resilience.

-

Data Strategy:

- Requirement: Each service should own its data store within its bounded context. Embrace eventual consistency where strong transactional consistency across services isn’t strictly necessary.

- Why: Shared databases are the fastest way to create a distributed monolith. Data autonomy is key to service independence.

-

Skills and Expertise:

- Requirement: Invest in training for engineers and architects in distributed systems design, cloud-native patterns, containerization, and domain-driven design.

- Why: Building and operating microservices requires a different skillset than traditional monolithic development.

-

Budget and Resources:

- Requirement: Be prepared for a higher initial investment in infrastructure, tooling, and potentially more cloud resources due to increased service instances.

- Why: The operational complexity of microservices comes with a cost.

Practical Considerations and Best Practices

Regardless of your chosen architecture, applying sound engineering principles is crucial.

- Start Simple, Evolve Smart: If unsure, begin with a modular monolith. It’s easier to break a monolith into microservices than to untangle a distributed monolith.

- Embrace Domain-Driven Design (DDD): Use bounded contexts to identify clear service boundaries. This is fundamental for avoiding the distributed monolith anti-pattern.

- Automate Everything Possible: CI/CD, testing, infrastructure provisioning, deployments, and rollbacks. Automation is the lubricant of microservices.

- Design for Failure: Assume services will fail. Implement resilience patterns like circuit breakers, retries with exponential backoff, bulkheads, and fallbacks.

- Prioritize Observability: Invest heavily in robust logging, metrics, and distributed tracing. You cannot effectively manage what you cannot see.

- Prefer Asynchronous Communication: Use message queues and event buses for loosely coupled service interactions, especially for non-critical paths. This improves resilience and responsiveness.

- Utilize API Gateways: Centralize cross-cutting concerns like authentication, authorization, rate limiting, and request routing at the edge of your microservices ecosystem.

- Consider a Service Mesh: For complex microservice deployments, a service mesh (like Istio or Linkerd) can handle traffic management, security, and observability at the network level, offloading these concerns from application code.

- Polyglot Persistence (Wisely): Allow services to choose the right database for their specific data model and access patterns, but avoid database sprawl without good reason.

- Test Thoroughly: Beyond unit tests, emphasize integration, contract, and end-to-end testing to ensure services communicate correctly and the system behaves as expected.

Conclusion

The debate between microservices and monoliths isn’t a battle to declare a single victor; it’s an ongoing exercise in informed decision-making. There is no universal “best” architecture. The optimal choice depends on a confluence of factors: your organization’s size, team structure, technical expertise, project complexity, scalability requirements, and time-to-market pressures.

A monolith offers initial simplicity and faster development for smaller, less complex systems, allowing teams to focus on delivering business value quickly. Microservices, while introducing significant operational complexity, provide unparalleled scalability, flexibility, and independent deployability for large, evolving, and high-traffic applications, especially when supported by a mature DevOps culture and skilled engineering teams.

Ultimately, the journey from a monolithic application to a microservices architecture is an evolutionary one. Start simple, understand your pain points, and incrementally adopt distributed patterns when the benefits clearly outweigh the costs. By understanding the advantages, disadvantages, and critical success factors for each approach, engineers and architects can make strategic choices that empower their teams to build robust, scalable, and maintainable software systems that stand the test of time.